DIAGNOSIS (2/3): Why higher fares, fewer seats and declining demand now reinforce each other. Nigeria’s domestic aviation market is often described as behaving irrationally. Demand weakens, yet fares rise. Capacity contracts, yet operating costs remain stubbornly high. Passengers feel priced out, airlines appear unresponsive, and policymakers struggle to reconcile the contradiction.

This is not irrational behaviour. It is a pattern.

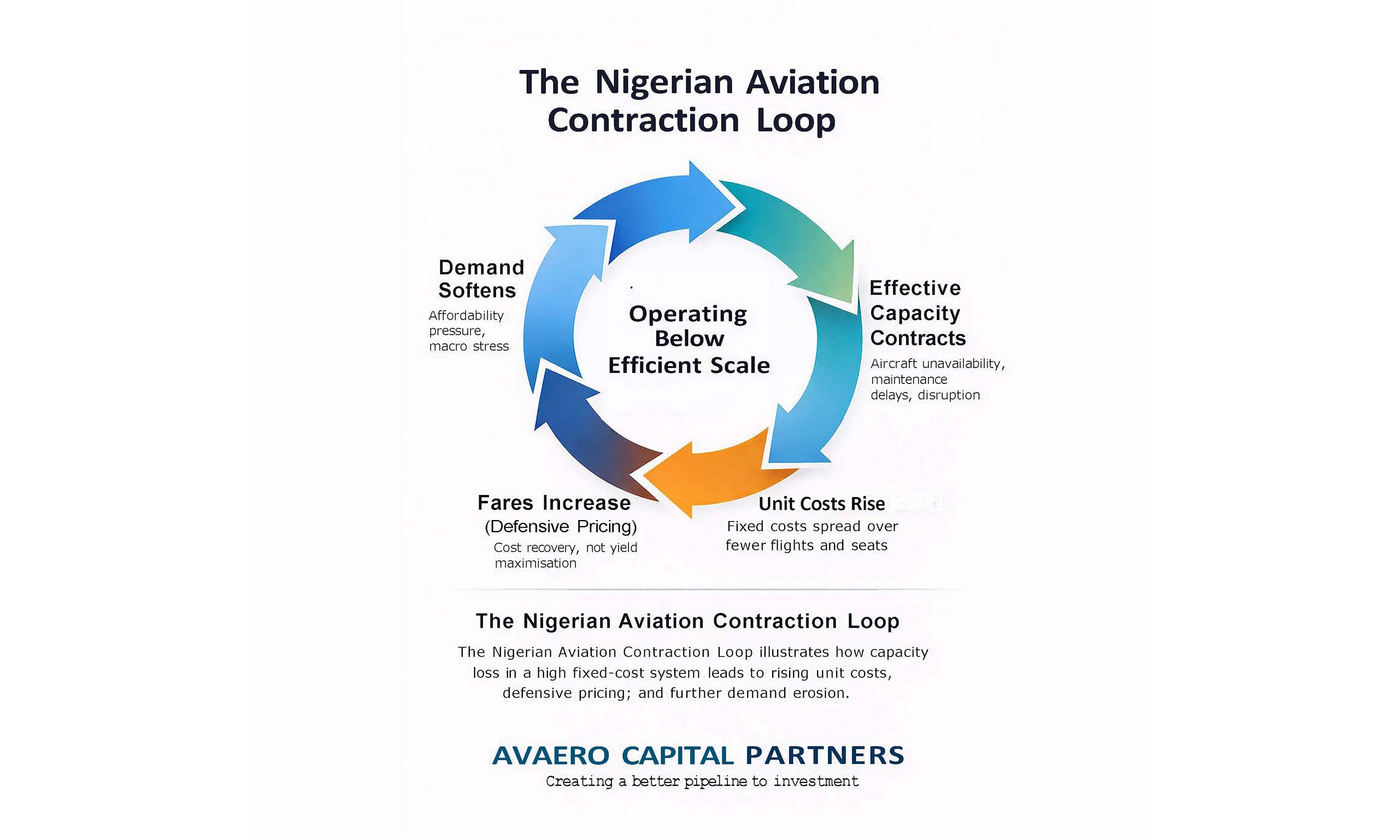

Avaero describes this pattern as the Nigerian Aviation Contraction Loop — a self-reinforcing cycle in which weakening demand, constrained capacity and rising unit costs interact in a way that suppresses recovery rather than enabling it. Until this mechanism is explicitly recognised, most responses will continue to focus on symptoms rather than causes.

In a textbook market, falling demand should lead to falling prices. Lower prices stimulate consumption, volumes recover, and equilibrium is restored. That logic depends on three conditions: flexible cost structures, excess capacity, and pricing freedom.

Nigeria’s aviation market operates under none of these conditions.

Instead, it is characterised by high fixed costs, limited aircraft availability, FX-linked inputs, and low tolerance for disruption. Under these constraints, price does not function as a demand-clearing signal. It functions as a cost-recovery mechanism. When demand softens, airlines are not left with spare, low-cost capacity waiting to be filled. They are left with the same cost base spread across fewer flights and fewer seats.

How the contraction loop actually works

What the diagram captures is not airline behaviour in isolation, but the economics of a high fixed-cost system operating below efficient scale.

When effective capacity contracts, costs do not fall with demand. They rise. Crew, maintenance exposure, insurance, handling, financing and disruption recovery are spread across fewer flights and fewer seats. Unit costs increase mechanically, even if airlines make no strategic changes at all.

Pricing then becomes defensive by necessity. Fares rise not to maximise yield, but to recover costs in a system that can no longer dilute them through volume. Higher fares worsen affordability, pushing more passengers out of the market entirely. Demand weakens further, reinforcing the contraction rather than correcting it.

This is the Nigerian Aviation Contraction Loop: a system-level feedback mechanism in which capacity loss, rising unit costs and defensive pricing suppress recovery, even when underlying travel need remains.

Why airlines cannot simply “price their way out”

Airlines are often criticised for failing to stimulate demand through lower fares. In practice, they lack the structural freedom to do so. With high operating leverage, limited access to spare aircraft, weak disruption resilience and FX-exposed cost bases, fare reductions would accelerate financial stress without guaranteeing volume recovery.

In such environments, pricing becomes defensive rather than competitive — a well-documented outcome in capital-intensive, high fixed-cost industries operating below efficient scale.

Not unique — but unusually acute

Economists describe this phenomenon as hysteresis: when temporary shocks cause permanent changes in market structure. Routes are withdrawn, aircraft are redeployed, passenger habits change, and network depth erodes. Even when macro conditions stabilise, the system does not automatically return to its previous state.

Aviation markets with high fixed costs and network dependencies are especially vulnerable to this effect.Contraction loops have appeared before in aviation and other network industries: Latin American airlines during currency crises, Caribbean inter-island air services, regional rail networks in emerging markets, and utilities operating under cost-recovery constraints.

What distinguishes Nigeria is the convergence of pressures: cost inflation, productivity constraints, aircraft scarcity and demand erosion occurring simultaneously, with limited buffers to absorb shock. This raises the risk of hysteresis, where temporary disruptions cause permanent market shrinkage through route exits, fleet redeployment and lasting changes in passenger behaviour.

Why the loop does not self-correct

Left alone, contraction loops do not resolve neatly. They harden.

Routes are permanently withdrawn. Aircraft are redeployed to more stable markets. Passenger habits change. Network depth erodes. Temporary shocks become permanent market shrinkage — a phenomenon economists describe as hysteresis.

This dynamic is consistent with economic hysteresis

Economically, this behaviour is consistent with hysteresis — a condition in which temporary shocks cause permanent changes to market structure. In capital-intensive transport sectors, lost capacity does not automatically return when conditions stabilise. Aircraft are redeployed, routes are abandoned, passenger habits change, and network depth erodes. As a result, recovery does not simply reverse the path of decline; it restarts from a smaller base. This is why contraction loops persist even after the original shock has passed.

Market forces alone will not break this cycle. Price signals cannot restore equilibrium when prices themselves are constrained by cost recovery.

What actually breaks a contraction loop

International experience shows that contraction loops do not self-correct. Left alone, they deepen.

Breaking the loop does not begin with pricing intervention. It begins with restoring the conditions under which pricing can once again respond to demand:

- lowering the structural cost floor through productivity gains and reduced timing failures,

- restoring system resilience so shocks do not immediately translate into capacity loss,

- and stabilising expectations so airlines can credibly plan for lower costs and higher reliability in the future.

Only under those conditions can pricing shift from cost recovery back toward demand-led competition.

Why naming the loop matters

The Nigerian domestic aviation market is not broken. It is constrained.

Until the contraction loop is addressed at a system level — by lowering the cost floor, restoring operational resilience and enabling airlines to operate at scale — pricing outcomes will continue to reflect constraint rather than competition.

Understanding the loop is not an academic exercise. It is the prerequisite for designing interventions that actually work.

This is article two in a three part series – related Avaero Insights articles:

Article 1: ANALYSIS: What Nigeria’s Aviation Capacity and Pricing Data Is Really Telling Us

Article 2: DIAGNOSIS: The Nigerian Aviation Contraction Loop

Article 3: SOLUTIONS: Breaking the Nigerian Aviation Contraction Loop

About the Author

Sindy Foster is Principal Managing Partner at Avaero Capital Partners, an aviation advisory firm focused on strategy, economics and operating performance across African and emerging aviation markets.

Her work centres on the structural drivers of airline performance — including capacity, pricing, operational resilience and system design. She advises airlines, investors and public-sector stakeholders on translating operating constraints into sustainable commercial outcomes.

Disclaimer: The insights in this article are for informational purposes only and do not constitute strategic advice. Aviation markets and circumstances vary, and decisions should be based on your organization’s specific context. For tailored consultancy, contact info@avaerocapital.com.